In small democracies without strongly established political parties, one of the significant challenges facing candidates for elected office is how to raise a significant profile with the electorate. One way to develop a high profile for public office is to be seeking re-election having just held the office: one manifestation of a complex phenomenon discussed globally as “the incumbency effect”. How far does this play out in the Manx context? Do sitting MHKs have a greater chance of being elected than their opponents?

The short answer is yes, to an important degree, demonstrated in every General Election for a hundred years.

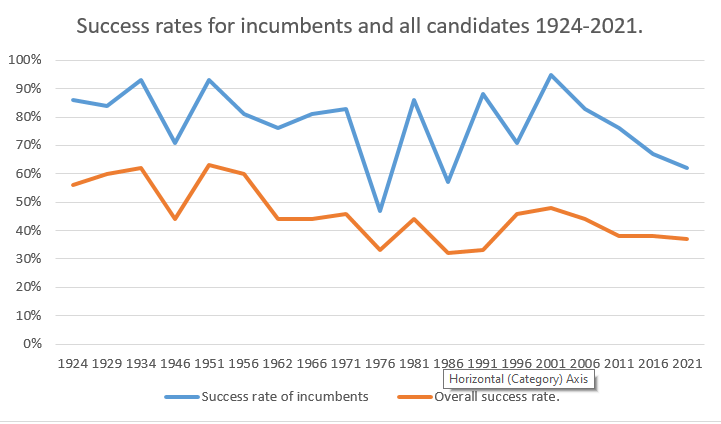

Although there is a sustained difference between the two success rates, it has fluctuated over the years. The smallest difference was in 1976, when there was a significant rejection of incumbents: 17 MHKs of 24 sought to retain their seats, and 9 were rejected by the electorate. Even that year incumbents were re-elected at a 47% rate, while 33% of candidates generally were elected. The twenty-first century started with a singularly stable House of Keys: the 95% success rate for incumbents was with a very high number of incumbents standing. 18 of 24 Keys retained their seats, with only one who sought to be elected being rejected by the electorate. From that exceptionally high level, however, the success rate of incumbents has decreased in every 21st century General Election, while the success rate of candidates generally has dropped much less dramatically.

Nonetheless, despite these fluctuations, there is a consistent pattern of sitting MHKs having a better chance of being elected than their non-sitting peers. If we average the success rates across all the General Elections, we find 78% for incumbents, and 46% for candidates as a whole. This difference is not dissimilar from the 20 percentage point advantage estimated for UK elections, and the 18 percentage point advantage described for Irish elections. Studies of larger democracies, however, tend to identify incumbency as party retention of a seat, not individual retention of a seat. The “personal incumbency advantage” may be low in party systems, but will often constitute the entire incumbency advantage in the Manx system.

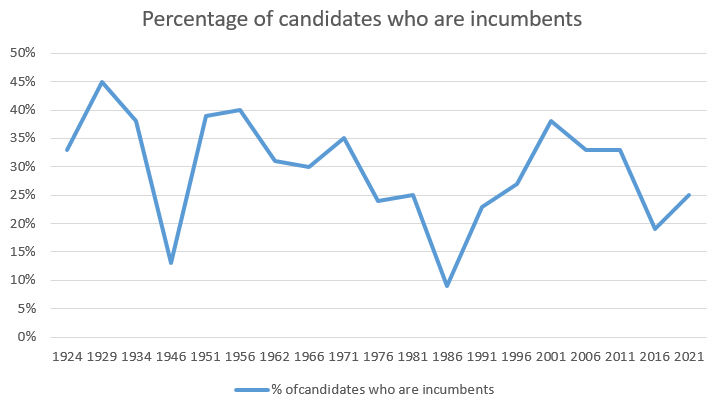

This differential success rate operates in a context where significant numbers of incumbents stand for re-election. It is useful to depict this in both absolute numbers (so how many incumbents stood), and percentage terms (so what percentage of candidates were incumbents).

A consistently high proportion of candidates are incumbents. Two General Elections stand out as having a much lower proportion than normal. In 1946, only 13% of candidates were incumbents. The previous General Election had been held in 1934, and most of the Keys had served for eight years, including six years of global war. Incumbents may have chosen not to stand because they did not wish to continue this form of public service even longer, or because of their assessment of the electorate’s desire for change. The proportion in 1986 was even lower, with only 9% of the candidates under the new electoral system being incumbents, and their success rate being comparatively close to non-incumbents (57% vs 32%). Incumbents may have considered that changes to the electoral system made it more difficult to assess their chances of success, or to manage their campaigns. There is a – less pronounced – drop in the percentage of candidates who are incumbents in other General Elections where there have been changes in the electoral system (for instance 2016).

One point to bring out is how often the electorate have been offered the option to have a House of Keys composed of a majority of incumbents, and the times that has actually materialised. A majority of Keys seats were contested by an incumbent (interpreting the term widely when there has been a change of the number of seats or the voting system, discussed more fully below) in every General Election except 1946 (when only 7 incumbents of the long House of Keys which had been elected in the pre-war election of 1934 contested the election), 1986 (when in a radically different electoral system only 7 incumbents contested the election), and 2016 (when in the first elections to 12 two member constituents, 12 incumbents stood). Half or more of the Keys consisted of incumbents following every General Election except 1946, 1976, 1986 (the first election under a very different electoral system), 1996 (the first election after the return to first past the post), and 2016 (the first election under the 12 2 seat constituency system).

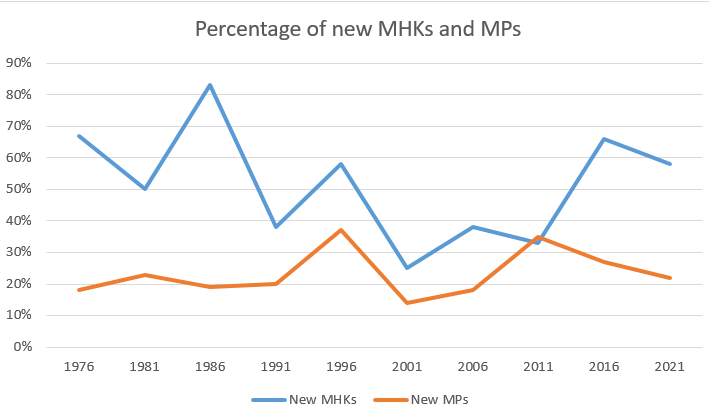

That sounds like a very significant number of seats held by incumbents across the century. We can, however, easily compare the proportion of new MPs in the UK Parliament and new MHKs in Tynwald for 1979-2019. Mapping the UK General Election onto the closest Manx General Election we find:

When contrasted with the larger, party institutionalised, neighbouring system, it is striking how much more volatile membership of the House of Keys is compared with the House of Commons. Only in 2011 (Keys) and 2010 (Commons) do we find a similar proportion of new members to the House: 33% in the Keys compared to 35% in the Commons. This was an exceptional point however – overwhelmingly, a higher percentage of the Keys are sitting for the first time as opposed to the Commons. In the period 1976-2021, in 5 of the 10 comparator points, more than half of the Keys were sitting for the first time; the highest percentage of new MPs sitting was 37% in 1997, followed by 35% in 2010 – in both cases, reflecting a change of the majority party in the Commons. Widening the scope slightly, the record number of new MPs elected in the 1945 election, 51%, would be completely unexceptional on the Manx scene since 1924.