The PHR (Amendment) no.16 makes significant changes to a number of aspects of the PHR. Unusually for PHRs, it was put before Tynwald before it was planned to come into effect on the 24th of July. The July Tynwald was tremendously busy, however, and this item was placed as the only substantive item on a supplementary order paper. A vote to suspend standing orders to allow this supplementary order paper, and so voting on this PHR, failed. Tynwald returned to it – for technical reasons as PHR no.17 – on the 23rd of July. After a long debate, the amendment passed.

A number of minor drafting errors are corrected, for instance replacing “in accordance” with the better “in accordance with”. A number of substantial changes are made however.

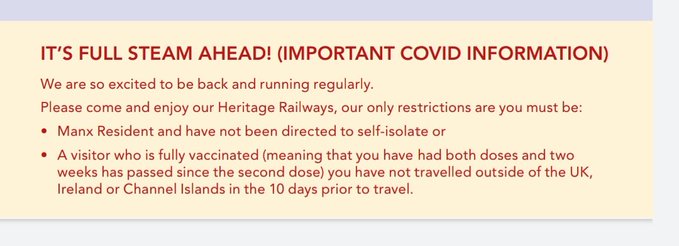

One criticised element of the initial version of the vaccination exemption for entry into the Isle of Man was that it was based on an unnecessarily narrow idea of what fully vaccinated could be, assuming as it did 2 doses of a vaccine being required. The Amendment changes the “2+2 vaccination exemption” to the “vaccination exemption”, making substantial changes in the process.

Formerly, the “2+2 vaccination exemption”, did not recognise single dose vaccines. The vaccination exemption now requires completing “the full course of a qualifying vaccination” (reg.5A(2)(a)), followed by the passing of “the relevant period” (formerly a set two weeks). Additionally, the vaccination exemption now applies to those participating in a qualifying clinical trial (reg.5A(2)(a), to be recognised by CoMin under reg.5A(3)(c)). The vaccination or trial must have taken place in a “relevant country” (formerly qualifying country). This continues to include the Common Travel Area, but is extended to Category 1 or 2 territories (which I discuss in a moment), and any other country specified by CoMin. There is no power for CoMin to declare a country that meets these requirements is not a relevant country – so CoMin could expand the list, but not restrict it. In fact, a different feature of the PHR means this is not a problem.

Formerly, the exemption was only available to those who had not travelled outside the common travel area in the 10 days preceding their arrival in the Island. This has been expanded beyond the Common Travel Area to the CTA “or a category 1 or Category 2 country or territory” (reg.5A(2)(c)). The list of Category 1-3 territories is tied to the relevant English Regulations, but CoMin can by direction vary these categories, for instance deciding that a territory in Category 3 in the English Regulations is to be treated as Category 2 (new reg.5(10)). This means, obliquely, that CoMin can remove a territory from being a relevant country for vaccinations, by moving it out of Category 1 or 2. The power to vary category can apply to “any part” of the PHR as well as the PHR as a whole. So if, for instance, CoMin wished to allow travel from Malta, but not recognise Maltese vaccinations for some reason, the power could be exercised only for the relevant country element.

The exemption still requires that a person not have travelled outside this expanded area in the ten days before they entered the Isle of Man, regardless of when that was. I still think it would be useful to think about how to deal with non-travelling vaccination exemptions.

In relation to children travelling with parents and guardians entitled to the vaccination exemption, changes bring it in line with the changes to the vaccination exemption (for instance the expansion beyond the Common Travel Area). The most significant change, however, is in relation to age, with the upper limit for a child to take advantage of this exception without any testing being raised from 5 to 12 (the exclusion of Category A persons under 5 years from Schedule 2 is similarly moved to 12 year olds). A child of 12 or over could take advantage of this exception only with testing within 48 hours of arrival and then again on the sixth day following arrival. The problem I pointed out earlier, that there was no discussion of the situation of a child who refused to test, has been dealt with: a child who does not provide a biological sample “must self-isolate as directed by the Director of Public Health” (new reg.5B(5)).

A change of age is also to be found in relation to contact tracing. Under the Amendment, the Director of Public Health can no longer require a person under 12 to self-isolate under reg.15 (reg.15(1)(b) as amended). In giving a direction notice requiring self-isolation, the Director of Public Health would now insert the relevant information from Schedule 2 into that direction notice (reg.15(12)). Once a direction notice has been issued, the Director of Public Health is able to revoke or amend it – a power I think implicit in this section already, but as it appears to have been one that has been exercised as a result of the policy shift in relation to self-isolation under track and trace, one whose explicit inclusion is understandable (new reg.15(4)). Similar changes can be found in the requirement to isolate when suspected to be infected, a power which the Director retains for those under 12 (reg.16); and to the power to require a Category C person to self-isolate, which however, no longer extends to those under 12 years of age (reg.18(2) as amended).

The House of Keys election.

Two points discussed in the July Tynwald, only one under this PHR.

It will be recalled that the last amendment to the PHR specifically dealt with the amendment of the PHR while the House of Keys was dissolved, and so Tynwald could not necessarily approve amendments of a PHR. This power was initially limited to self-isolation requirements and periods, and samples and analysis. This has been expanded to allow a direction to “vary the application of any part of these Regulations” (new reg.9A(3A)). It remains limited to the period during which the Keys is dissolved, and subject to consideration at the first sitting of Tynwald following the day on which the House of Keys is first assembled.

In the same sitting, Tynwald approved the Elections (Keys) (Amendment) Regulations 2021. Existing regulations meant that an application for a proxy vote justified by a medical emergency had to be received by Friday 17 September. Mid-pandemic, however, a medical emergency might arise for a number of electors after this date, but before polling day. These Regulation would allow a person to appoint a proxy to vote on his or her behalf up until 22 September – the day before the elections.

Schedule 2.

During the Tynwald debate, there was some discussion of the detailed changes to Schedule 2, so I have added this (detailed) discussion here.

A number of changes were made in Schedule 2. A common theme is the removal of restrictions in the Schedule on non-emergency access to health and social care settings – this is not to say, of course, that individual direction notices may not include restrictions effectively recreating this limit.

Category A persons (residents of the Isle of Man returning from the Common Travel Area), are expanded to include those returning from Category 1 countries or territories. Category B persons are similarly redefined to exclude residents who have not travelled outside the CTA or Category 1 territories. Both types of returning residents would no longer be restricted in attending health or social care premises within ten days of their return.

Category C persons (non-residents permitted to enter who have not travelled outside the Common Travel Area), are expanded to include those returning from Category 1 countries or territories. Category D persons are similarly redefined to exclude those who who had travelled only in Category 1 countries or territories. In both cases, the person would no longer be restricted in attending health or social care premises within ten days of their return.

Category I persons – that is persons who are reasonably suspected of being infected – have the default self-isolation period dropped from 21 days to 10 days, and may test on the day of being given a direction notice to self-isolate, rather than on or after the ninth day of being given the direction notice. A Category I person who tests negative is no longer required to self-isolate.

Category J persons (contact traced persons who share a household with an infected person) similarly have the default self-isolation dropped to 10 days, and may test on the day of being given a direction notice, rather than on or after the ninth day. Where the sample is negative, the person may exercise, but otherwise must self-isolate as directed by the Director of Public Health. The explicit restriction on attending health or social care premises within ten days of their test would no longer apply. A Category J person, and their household, who has tested positive must self-isolate as directed by the Director of Public Health.

Category K persons (contact traced persons who do not share a household with an infected person) similarly have the default self-isolation dropped to 10 days, and need only test once. If they test negative, they may exercise, but otherwise must self-isolate as directed by the Director of Public Health. There was formerly a reference to the consequences of a positive test, but this has now been deleted.